Scotch Malt Whisky is made in pot stills from just water, barley and yeast. It is a complicated procedure but basically the traditional method is as follows.

Barley is the basic ingredient of whisky.

|

In the mash tun, the dried malt is mashed with hot water to make the wort.

|

Barley is steeped in water for two or three days, which causes it to start germinating when it is then spread on a maltings floor. Heat is given off and the barley is regularly turned with wooden paddles called shiels to enable even development. Starch in the barley grains turns to sugar over about 12 days, at which time germination is stopped by drying in a kiln. Usually part at least of the drying is by peat-fuelled fires, the smoke from which imparts smoky, peaty aroma and flavour to the malt and the final whisky. This is called peat reek and can be light or very heavy according to the chosen style. However, one distillery, Glengoyne, closes off the kiln-smoke from the malt so that no smokiness goes into the whisky.

The dried malt is ground into grist and mashed (mixed) together with hot water to make a sugar-rich liquid called wort. It is drawn off and the solids left behind are collected for use as cattle feed. (Quite a few distillery herds have won Supreme Championships at Smithfield over the years.) The wort has yeast added to it, which then ferments over two days into a weak ale called wash.

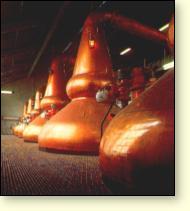

Most pot-still whisky is distilled twice so stills tend to be grouped in pairs comprising a wash still and a spirit still. There are a few distilleries where a third still is used either to allow more complicated production methods (e.g. Springbank) or for triple distillation (e.g. Auchentoshan). With double-distillation, the wash is loaded into the wash still which is heated (sometimes with a naked coal or gas flame, usually these days with internal steam pipes) to slow boiling. Alcohol vapours boil off, pass over the still’s swan-neck and condense (rarely now in a ‘worm’ immersed in cold water, usually in a modern condenser) to a liquid, called low wines. The low wines are then loaded into the spirit still and distilled a second time.

As the distillate begins to run off, the early part is unwholesome and steered to a side tank by the stillman watching the liquid pass through the spirit safe. At the right moment, he diverts the flow and collects the next part of the run in the main container which is called the spirit receiver.

The stillman must continue to watch because while the liquid runs off the still, its alcoholic strength gradually drops. When a fixed strength is reached the flow is once again turned away to the side tank until it peters out, almost as water. The ‘middle cut’ – the ‘heart’ of the run that was collected in the spirit receiver – is the clean, wholesome distillate which goes on to become whisky. Nothing is wasted. The foreshots and feints that were collected separately are added to the next batch of low wines and distilled with them.

Scotch Grain Whisky is made in continuous stills from assorted unmalted cereals and a proportion of malted barley. The unmalted grains are cooked so that the starch cells burst open. When they are mixed with the malted barley to make a mash, the starch turns to sugar and a wort is created as with malt whisky production.

The fermented wash is fed in a constant flow to a patent still which completes both the evaporation and condensation processes within its analyser and rectifier columns. As long as wash is fed in, spirit comes out at the other end. The grain spirit is produced at much higher strength, making it smooth in texture but faint in both flavour and aroma.

Both malt and grain whisky must age in oak casks for a legal minimum of three years, but in fact most ages for much longer. The majority of single malts mature for between eight and 16 years, and 12 years is widely used as the bottling age for both malts and good de luxe blends. If an age is declared on a label it refers to the youngest whisky blended or vatted in the bottle.

During ageing, whisky loses its youthful fieriness and takes on flavours and aromas from the cask. Vanilla and a pleasant oakiness are two such, and, if the cask has previously held sherry, sweetness, toffee and sherry flavours may also come through. With a range of characteristics on call, the best whiskies achieve a balance of mellowness, complexity and completeness that is most attractive.

Blended Scotch assembles the best degrees of whisky’s richness, flavour, aroma, texture, mellowness and strength without the more daunting extremes of pungency, concentration, high strength, ultra-smokiness or blandness. Blended Scotch has nothing in common with, say, blended wine or blended whiskey from other countries where something acceptable is made out of constituents that are unbalanced or flawed. Most of the whiskies used in blended Scotch are available as self whiskies in their own right. Good blends have from 45% to 60% malt content and the skills needed to assemble perhaps 45 different whiskies to make a single consistent blend are considerable.