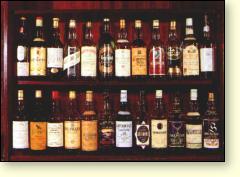

Scotch whisky divides into three main styles: malt, grain and a blend of these two.

Scotch whisky divides into three main styles: malt, grain and a blend of these two.

• Malt Whisky has specific, sometimes very pronounced, flavours and aromas which come from the malted barley, the amount of peat used in drying it and, once ageing is completed, the type of wood in which it matures. The range of character goes from deep, pungent, smoky and earthy to light, subtle, gentle and sweet. A single malt is the whisky produced by an individual distillery. A vatted malt is a blend of malts from two or more individual distilleries.

• Grain Whisky is easier, and hence cheaper, to produce and its quieter personality makes it often, but not always, less interesting as a self whisky. Grain spirit matures rapidly so tends to need less ageing than malts. Most grain whisky is used in blending to soften and lighten the final product but there are two distilleries which put stated-age single grains in bottle, one of these launched quite recently.

• Blended Whisky is a blend of both malt and grain whiskies. Each brand of blended whisky is made to a specific, secret recipe and well-known brands like Famous Grouse and Bell’s have many different single distillates in their make-up.

Types of Still

• A Pot Still is simply a large kettle, which is filled to a certain capacity with wash so it can be boiled off. The alcoholic vapours rise to the top of the swan-neck, pass over and run through cold pipes which condense them back to liquid. A first distillation creates a liquid of about 8 per cent alcohol by volume. Most pot-still production is by double-distillation and after the second distilling run the spirit reaches about 70 per cent alcohol by volume.

• A continuous still is a more complex machine, which ingeniously combines the boiling and condensation processes in tall rectification towers so that spirit is produced in a continuous flow. Distillate from a continuous still is usually high in strength and smooth in texture; a drawback, however, is that most of the flavouring elements are lost. Alternative names for these stills are ‘patent’ or Coffey, the latter after the Irish Exciseman who developed the original idea; Stein, the Scottish inventor of the continuous process, receives scant credit today for his achievement.

Different Kinds of Barrel

The spirit is left to mature in wooden barrels in the distillery warehouses.

|

The oak barrels in which Scotch ages mostly come from Spain and the USA. The Spanish casks are brought over from Jerez and have previously been used to ferment and/or store sherry, usually oloroso. This imparts a rich, sweet finish to the whisky, accounting for as much, some say, as 50 per cent of the final flavour and texture. The traditions of using Spanish sherrywood go back a long way to the days when sherry was imported in barrels and bottled here. The sherry overlay on the whisky became such an accepted part of the style that the interiors of non-sherry barrels were often coated with cooked wine concentrates called paxarete before being filled with new spirit. This is no longer done.

Those casks brought from the USA have previously held bourbon. Since by American law each can only be used once, they become redundant as soon as they are emptied for the whiskey to be bottled. Scotch companies that prefer not to use sherry casks mature spirit in ex-bourbon wood, because subtler natural flavours in their whiskies can show through more readily.

Very few distillers use all-sherry or all-bourbon wood, most deciding on a (secret) combination of the two. Further subtleties may be achieved by using casks that have been filled with Scotch once, twice or three times before. With each filling, the influence that a cask can have on the whisky is diminished.

Regional Classification of Whisky Styles

If Malt whisky were French it would, like wine and cognac, be legally divided into a dozen or so appellations contrôlées based on features such as analysis of water supply, specified barley types, and peat content in parts per million. The classification that actually exists is a conventional four-part division which has only recently become properly useful by the adoption of certain sub-divisions.

Highland is the largest and most diverse category comprising the mainland and islands (except Islay) north of a line drawn diagonally between the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Tay. Although there are earthy, full-throated exceptions – especially near the coasts – the whiskies are mainly light/medium-weight and fragrant.

Two important sub-divisions are Speyside and Island. Speyside is the area around the River Spey and tributaries in the north-east. Gentle, green, fertile countryside that yields richly aromatic and flavoured malts within a light-to-medium and well-balanced framework. Very elegant with good complexity.

Island includes the inner islands off the west (Jura, Mull and Skye) and north (Orkney) coasts of Scotland, where style includes Highland elegance but stretches to full-bodied smoky peatiness, concentration, spiciness and a zest of salty ozone.

An addition to this group is pending with the scheduled completion of a new distillery on the island of Arran. It is to be the island’s first for 150 years.

• Lowland malts are from the mainland to the south of that Highland Line mentioned above. They are soft and understated, often sweet, smooth and whispery malts with faint delivery in peatiness compared to any of the other categories.

• Islay is a category in its own right due to the pungent, concentrated and peaty earthiness of the traditional style of whisky produced there. Tasters speak of seashore and even medicinal dimensions to the richness of the prevailing character yet the whiskies have their own remarkable structure and balance. Despite its particularity, traditional Islay whisky is becoming very popular outside Scotland, although some distillers are choosing to lighten the style in the brands they produce.

• Campbeltown is such a diminished category now that it is shared by only two distilleries producing three whiskies; it used to be the second-largest grouping after Highland. The malts are rich and quite full-bodied with a distinct saltiness and medium-impact peat. When there were more distilleries it was regarded as a halfway house between mainland and Islay styles.

Peat

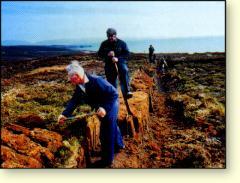

Cutting peat on the moor near Highland Park.

|

Looking across a peat bog on to mountains is to take a mental snapshot of the landscape as it was in prehistoric times. All that is likely to have changed in the view before you is the thickness of the carpet – 10 metres of depth takes about 8000 years to form. It is formed by the build-up of successive layers of seasonal fen vegetation which cannot decompose due to waterlogging and lack of oxygen. Peat occurs uniformly across the Scottish landcape so it is no surprise that it has long been the traditional household fuel. Its role in the Gaels’ whisky making was fortuitous since it was burned simply to dry the malted barley – what else were they going to use?

Early experimentation in generating electricity from a peat-burning turbine was carried out in 1959 at Altnabreac Bog in Caithness (about 30 miles west of Pulteney distillery). Peat is now used to fire power stations and, although it has about two-thirds of the calorific value of coal, the cost per unit of electricity generated is less than that of coal. As well as its use in whisky making, peat is used in the fish-curing industry in Scotland.